Putting the Proton Under a Microscope

What if you could peer inside a proton—something a trillion times smaller than a grain of sand?

That’s exactly what physicists do with Deep Inelastic Scattering (DIS). It’s one of our most powerful tools for exploring the hidden world inside protons and neutrons, and it’s about to enter a new era with the upcoming Electron-Ion Collider.

How Do You “See” Something So Small?

You can’t use a regular microscope to look inside a proton—visible light is far too large to reveal anything at that scale. Instead, physicists use a clever trick: they fire high-energy electrons at protons and watch what bounces back.

Think of it like throwing a ball into a dark room to figure out what’s inside. If the ball bounces straight back, you hit something solid. If it scatters at weird angles, maybe you hit something with complex structure. By carefully measuring how electrons scatter off protons, we can map out what’s going on inside.

Deep inelastic scattering: an electron probes the inside of a proton by exchanging a virtual photon. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The “deep” in Deep Inelastic Scattering means we’re probing deep inside the proton. The “inelastic” means the proton doesn’t stay intact—it breaks apart, revealing its inner contents.

What’s Actually Inside a Proton?

For a long time, scientists thought protons were fundamental—tiny, solid balls with no internal structure. DIS experiments in the late 1960s changed everything. They revealed that protons are made of even smaller particles called quarks, held together by force-carrying particles called gluons.

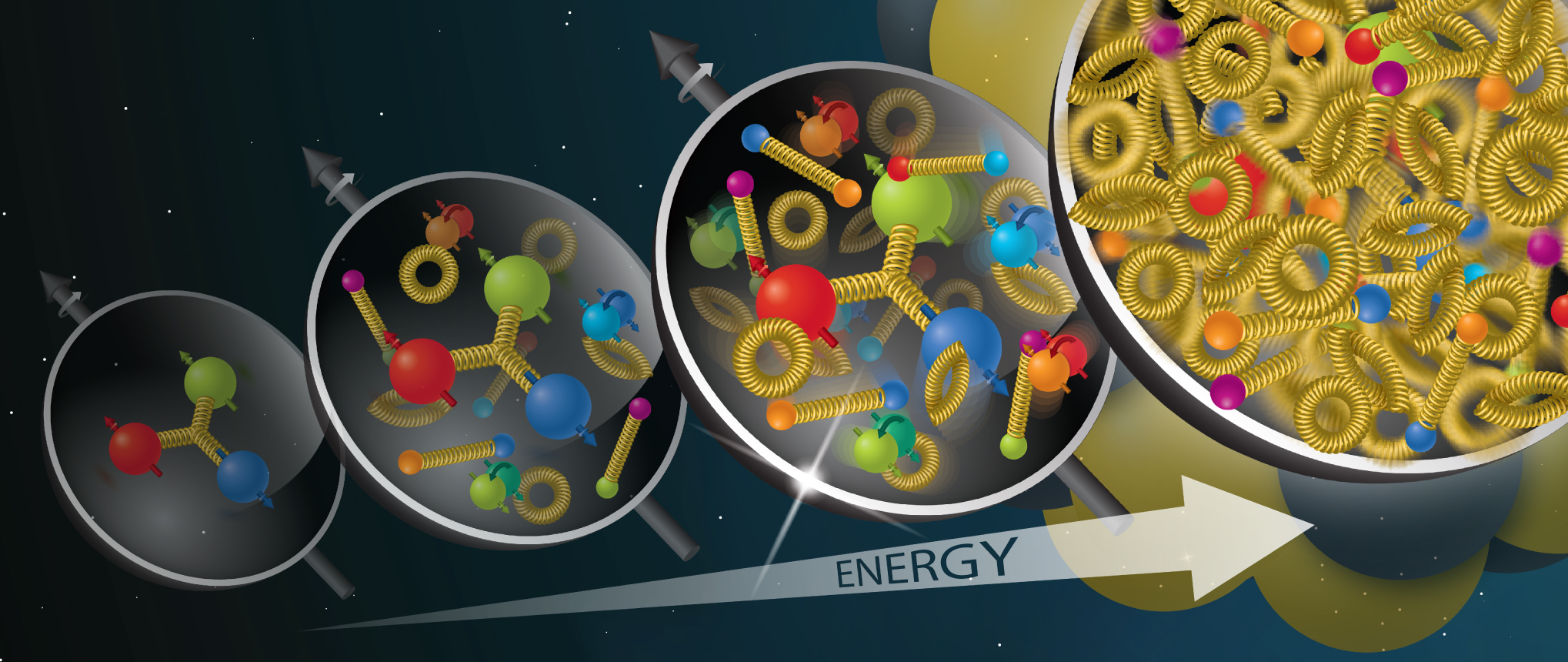

But here’s where it gets strange. The deeper you look, the weirder it gets. At low energies, a proton looks like three quarks bound together. But when you probe at higher energies, you start seeing a sea of gluons—and there seem to be more and more of them the harder you look.

One way to understand DIS is through the "color dipole" framework. When a high-energy electron approaches a proton, it sends out a virtual photon that briefly transforms into a quark-antiquark pair—a "dipole." This dipole then interacts with the gluons inside the proton, like a tiny probe sampling the proton's internal structure.

Gluon Saturation: When Things Get Crowded

Imagine packing more and more people into a room. Eventually, you can’t fit anyone else—the room is saturated. Something similar happens inside protons.

As we probe at higher and higher energies, we see more and more gluons. But there’s a limit. At some point, gluons start overlapping and interacting with each other so strongly that their growth slows down. This phenomenon is called gluon saturation, and it represents a completely new state of matter sometimes called the Color Glass Condensate.

At high energies, gluons inside nuclei begin to overlap and recombine, reaching a saturated state. Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory

We’ve seen hints of gluon saturation in experiments, but we’ve never been able to study it directly. That’s about to change.

The Electron-Ion Collider: A New Window Into Matter

The Electron-Ion Collider (EIC), currently being built at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, will be the world’s first facility specifically designed to explore gluon saturation and the internal structure of protons and nuclei.

By colliding high-energy electrons with protons and heavier ions, the EIC will let us:

- Map the gluon structure of protons with unprecedented precision

- Observe gluon saturation directly for the first time

- Understand how mass arises — gluons contribute most of a proton’s mass, even though they’re massless themselves

- Explore a new state of matter — the Color Glass Condensate

The EIC is expected to begin operations in the early 2030s, opening a new chapter in our understanding of the strong force—one of the four fundamental forces of nature.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding gluon saturation isn’t just about satisfying curiosity. The strong force holds atomic nuclei together, making atoms—and everything made of atoms—possible. By understanding how gluons behave at extreme densities, we learn something fundamental about why matter exists the way it does.

DIS gave us quarks. The EIC might give us something even more surprising.