Beyond Fisher Forecasting for Cosmology

When Standard Statistical Methods Fall Short

The Big Picture

Before building expensive scientific experiments—like space telescopes or particle colliders—scientists need to know: Will this experiment actually teach us something new? This is where forecasting comes in. By simulating what an experiment might measure, researchers can predict how precisely they’ll be able to determine important physical quantities before spending billions of dollars.

The Fisher information matrix has been the go-to tool for this forecasting for decades. It’s fast, elegant, and mathematically convenient. But it has a hidden weakness: it assumes the world behaves in a very specific way. When that assumption breaks down, Fisher forecasts can be dangerously misleading.

Our paper introduces a practical test to determine when you can trust Fisher forecasts—and when you need something more sophisticated.

Why Fisher Forecasting Works (Usually)

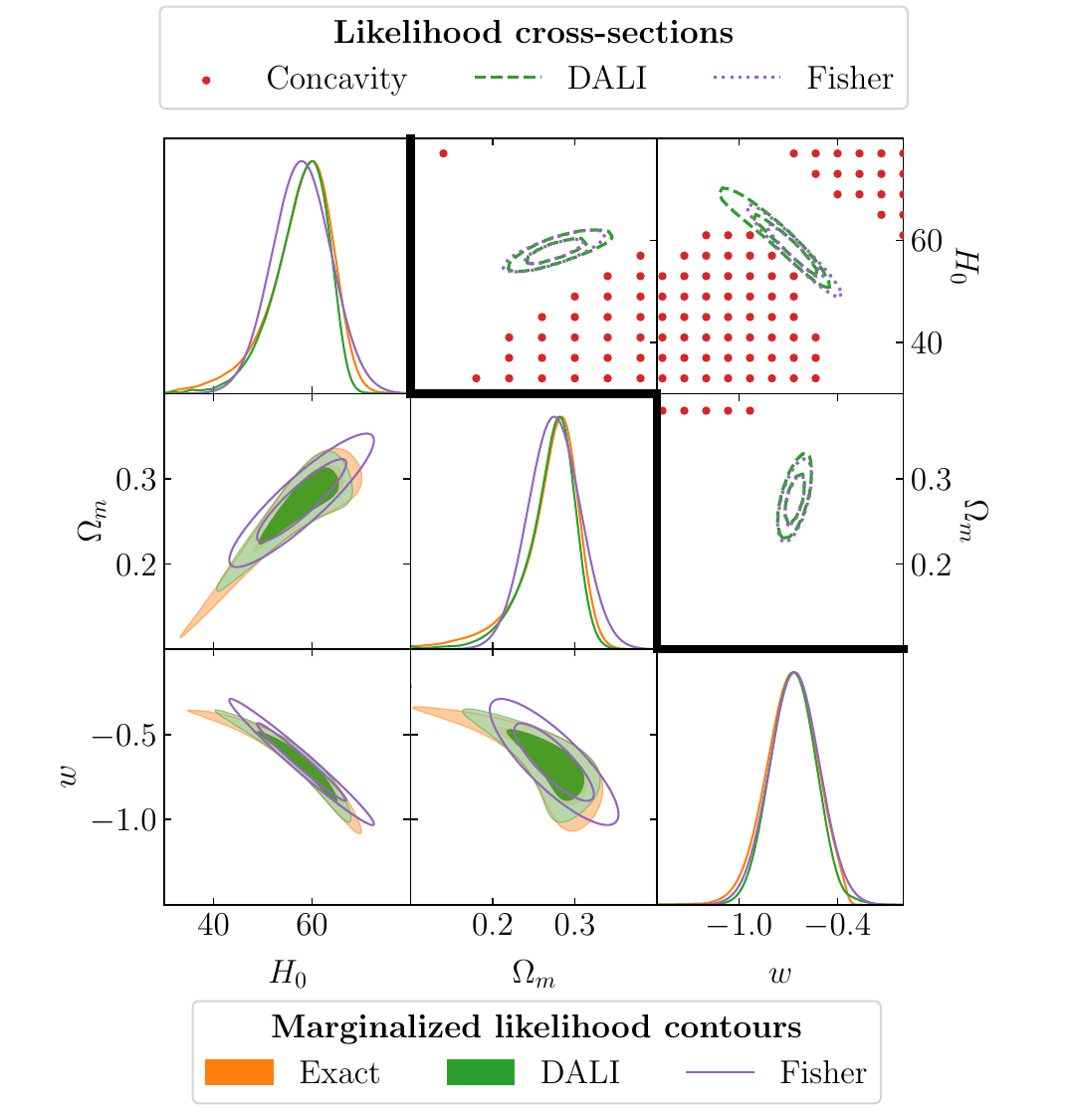

Imagine you’re trying to measure two quantities—say, the expansion rate of the universe (\(H_0\)) and the amount of dark matter (\(\Omega_m\)). Your measurements will have some uncertainty, and typically you’ll find that these uncertainties form an ellipse when plotted:

Comparison of Fisher (purple), DALI (green), and exact (orange) likelihood contours

The Fisher matrix captures this ellipse perfectly. It tells you:

- How uncertain each parameter is (the width of the ellipse)

- How parameters are correlated (the tilt of the ellipse)

- All with just \(\mathcal{O}(N)\) calculations for \(N\) parameters

This efficiency is why Fisher forecasting dominates cosmology. Computing a full forecast might take seconds instead of days.

When Fisher Fails: The Banana Problem

Fisher’s mathematical elegance comes from a key assumption: the likelihood (roughly, the probability distribution of your measurements) must be Gaussian—a perfect bell curve. This requires:

- Data are Gaussian distributed (often true for averaged measurements)

- Observables depend linearly on parameters (often not true)

When the second condition fails, something interesting happens. Instead of nice elliptical contours, you get banana-shaped curves:

The measurements still constrain the parameters, but not in the symmetric way Fisher predicts. The Fisher matrix will claim you can measure a parameter equally well in both directions, when in reality one direction is much better constrained than the other.

Real-world examples where Fisher fails:

- Weak constraints on cosmological parameters (early universe measurements)

- Strong parameter degeneracies (when parameters are highly correlated)

- Highly non-linear models (dark energy equation of state)

The DALI Solution

The Derivative Approximation for LIkelihoods (DALI) method extends Fisher forecasting by keeping more terms in a mathematical expansion. Think of it like this:

| Method | What it captures | Computation |

|---|---|---|

| Fisher | Elliptical (Gaussian) contours only | \(\mathcal{O}(N)\) evaluations |

| DALI | Curved, asymmetric “banana” contours | \(\mathcal{O}(N^2)\) evaluations |

| Full MCMC | Exact contours of any shape | \(\mathcal{O}(10^5 - 10^6)\) evaluations |

DALI introduces two additional tensors beyond the Fisher matrix:

\[G_{\alpha\beta\gamma} = \mu_{,\alpha\beta} M \mu_{,\gamma}\] \[H_{\alpha\beta\gamma\delta} = \mu_{,\alpha\beta} M \mu_{,\gamma\delta}\]These capture how the observables \(\mu\) curve with respect to the parameters, allowing DALI to detect non-Gaussian features that Fisher misses entirely.

Our Key Contribution: A Validity Test

Here’s the practical problem: Fisher forecasting doesn’t tell you when it’s wrong. You could be using Fisher to plan a major experiment, get beautiful elliptical forecasts, and have no idea that the real uncertainties are completely different.

Our paper provides a simple diagnostic:

Compare 2D slices of Fisher and DALI likelihood surfaces. If the DALI contours show concavity (curved inward like a banana), Fisher is likely failing. If they match, Fisher is probably reliable.

This test requires only the modest additional computation of DALI (not a full MCMC), making it practical to run alongside any Fisher forecast as a sanity check.

We validated this approach using:

- Expansion history data (BAO, cosmic chronometers, quasars)

- CMB power spectra (simulated Simons Observatory and CMB-S4)

- Primordial abundances (Big Bang nucleosynthesis measurements)

In each case, when our test flagged potential problems, comparison with exact MCMC sampling confirmed the Fisher approximation was indeed failing.

Practical Takeaways

- Don’t blindly trust Fisher forecasts for weakly constraining data or degenerate parameters

- Use our DALI cross-section test as a quick diagnostic before committing to expensive MCMC

- DALI isn’t always better—for sub-linear parameter dependence, it can perform worse than Fisher

- When in doubt, sample the exact likelihood, but now you have a way to know when doubt is warranted

Publication Details

Beyond Fisher Forecasting for Cosmology

Authors

Joseph Ryan, Brandon Stevenson, Cynthia Trendafilova, Joel Meyers

Institution

Southern Methodist University

Journal

Physical Review D 107, 103506

Published

May 8, 2023